The last display of the year at the Architecture and Planning Library pays homage to the humble (and not so humble) kiwi bach.

The last display of the year at the Architecture and Planning Library pays homage to the humble (and not so humble) kiwi bach.

Kiwi bach culture began in the 1920s and continues on today. Although new baches are generally a much grander affair than their forbears, they still retain the essential qualities of shared spaces that are multifunctional with the romance of “getting away” providing the opportunities to create memories that last longer than any structure might.

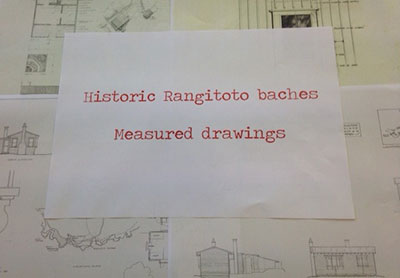

We can see these ideals preserved in the remaining historic baches on Rangitoto Island and our display includes measured drawings of some of these baches.

We can see these ideals preserved in the remaining historic baches on Rangitoto Island and our display includes measured drawings of some of these baches.

In 1854 Rangitoto was bought by the Government from Ngatipaoa to secure supply for stone needed for roading. By 1890 the island was governed by the Rangitoto Domain Board and under the provisions of the Public Domains Act 1883 it was classified as a reserve. Leases for existing quarries remained as they provided much needed revenue and indeed some of the baches were originally built as housing for quarry staff (Yoffe 2000).

In 1911 camping sites became available for lease but in 1918 this was stopped due to inadequate sanitation. From then on only permanent building sites were allowed as long as they provided appropriate sanitation (Yoffe, 2000). However, by allowing dwellings to be built the Domain Board were over reaching their authority by allowing private dwellings on public land. Regardless of this legality, the bach communities on Rangitoto continued to grow throughout the 1920s and 1930s until finally culminating into 140 baches (Kearns & Collins, 2006).

Logistical and economic limitations meant the baches were built using whatever materials were accessible and cheap (or ideally free). This resulted in many lease holders using salvaged materials from vessels that had been scuttled in the bays around Rangitoto. For example, the Ellis bach (Bach 96; measured drawing on display) has evidence of ship doors being used for the bedroom and outhouse doors (Bennett & Fowler, 2016).

1937 brought a halt to further baches being built as a Government review of the Public Reserves and Domains Act revoked the ability to erect dwellings and stipulated that lease holders had to vacant and remove their dwelling when their leases ended. They could neither develop nor sell the existing dwelling – effectively providing a snapshot of time in terms of culture and architecture. The majority of leases expired in the 1970s and 1980s and with ownership passing to the Crown demolitions began. When the Department of Conservation took over the administration of Rangitoto Island in 1987 a moratorium was placed on further demolition and an appraisal of their architectural, cultural and historic value was undertaken. Today 35 baches remain and a High Court ruling in 2004 recognised them as a community and as such, they are entitled to be protected (Kearns & Collins, 2006).

1937 brought a halt to further baches being built as a Government review of the Public Reserves and Domains Act revoked the ability to erect dwellings and stipulated that lease holders had to vacant and remove their dwelling when their leases ended. They could neither develop nor sell the existing dwelling – effectively providing a snapshot of time in terms of culture and architecture. The majority of leases expired in the 1970s and 1980s and with ownership passing to the Crown demolitions began. When the Department of Conservation took over the administration of Rangitoto Island in 1987 a moratorium was placed on further demolition and an appraisal of their architectural, cultural and historic value was undertaken. Today 35 baches remain and a High Court ruling in 2004 recognised them as a community and as such, they are entitled to be protected (Kearns & Collins, 2006).

Learn more

Fiona Lamont, Library Assistant, Architecture and Planning Library

References

Bennett, K. & Fowler, M. (2016). Rich pickings: An analysis of opportunistic behaviour at Rangitoto Island, Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 11(2), p. 179-196.

Kearns, R. & Collins D. (2006). https://catalogue.library.auckland.ac.nz/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_wj10.1111/j.1745-7939.2006.00075.x&context=PC&vid=NEWUI&search_scope=Primo_Central&tab=articles&lang=en_US. New Zealand Geographer, 62 (3), p. 227-235.

Yoffe, S. (2000). Holiday Communities on Rangitoto Island New Zealand. Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland.